Book Profile

“Pathological Altruism” May Kill a City Near You

Book Review of "San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities"

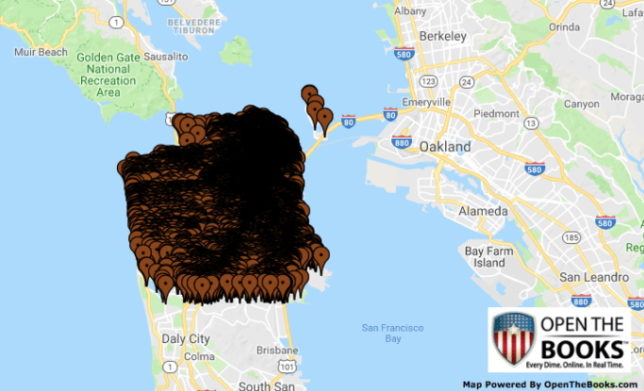

Human waste reportings in San Francisco, 2011–2019. Credit: Open the Books.

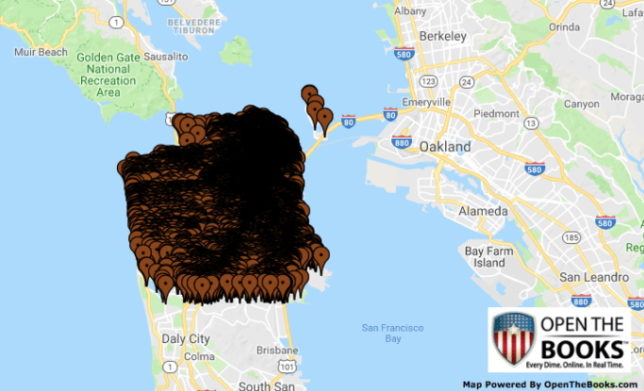

Human waste reportings in San Francisco, 2011–2019. Credit: Open the Books.

San Francisco had a public health crisis last year. But it’s not the one you’re thinking of.

Drug overdoses claimed 697 victims in the city during 2020, more than double the 257 COVID deaths over the same period. This was a 150 percent increase beyond San Francisco’s 2019 overdose deaths and three times the 2017 tally. Nationally, the story was just the opposite: The pandemic killed four times more Americans than drug overdoses last year, despite a historic high number of overdose fatalities nationwide.

The special disaster happening in the City by the Bay is literally a deadly case of “pathological altruism,” claims Michael Shellenberger, author of San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities.

As awful as they were, San Francisco’s narcotics fatalities were just the by-product of the town’s toxic policies. Shellenberger credits the politicians, poverty nonprofits, and other local officials with nurturing a dramatic spike in homelessness, an indifference to the breakdown of law and order, rampant sale of illegal drugs in public, and a total lack of accountability for failure.

“Homeless” Is a Harmful Word

San Francisco’s outsized homeless problem is intimately related to all of it.

According to Shellenberger, the ranks of the homeless across the nation fell during the 15 years leading up to 2020. The problem declined by 19 percent in Chicago, 32 percent in Miami, and 43 percent in Atlanta.

No such luck in the Bay Area, where the homeless population shot up 32 percent during the era.

The case made in San Fransicko is that the very word “homeless” is harmful. The book demonstrates the so-called homeless population—contrary to myth—is not comprised of hard-luck cases such as unemployed parents with children or battered women escaping abusive partners. Instead, the “homeless” are overwhelmingly those with serious mental illnesses, major substance abuse problems, pathological personal behavior, or a combination of all of these.

An unmedicated schizophrenic wandering madly alone through the world desperately needs a mental health intervention. The many street people suffering from drug addiction need substance abuse treatment. Even the slovenly selfish individuals living lives of petty crime and drug use because they can get away with it (and San Fransicko shows there are some of those as well) need to face the legal consequences of their decisions so they will consider a change of behavior.

These challenges need different solutions, and none of them should be remotely compared to a battered spouse needing temporary shelter. The word “homeless” is used to cover so much that it means nothing at all, says Shellenberger. Its use has allowed those managing the money spent on these different concerns to avoid accountability for failing to fix anything.

According to Shellenberger, California spends “50 percent more than the national average” for each patient receiving mental health services and yet parlayed this into a “30 percent higher rate of mentally ill people in jails, and a 91 percent higher rate of mentally ill people on the streets or in homeless shelters.”

The book concludes with a proposal to take all this money away from the government officials and nonprofits that have so badly mismanaged it. In its place, Shellenberger would create a single state official, appointed by and answerable to the governor, with the money, authority and (most importantly) total responsibility for addressing the out-of-control mental health, substance abuse, and other issues. On its face it seems to be a well thought-out and plausible solution.

Subjectively speaking, the current tragedy laid out in the book leaves a reader thinking that even a poo-flinging monkey could choose a more constructive policy than the mess currently in place.

The ACLU: Part of the Problem

Those suffering serious mental illnesses and addictions are often notoriously incapable of recognizing they have a malady. Their problems sometimes cannot be solved unless they are coerced (gently or otherwise) into accepting treatment.

And serious mental illnesses absolutely cannot be solved if they are misdiagnosed as a “lack of shelter.” But that is the response from too many supposed advocates for the “homeless” who recklessly relabel these complicated challenges as a simple inability to afford rent.

Squatting in tents in public parks, defecating in public (an astonishingly serious issue in San Francisco), committing petty thefts, and shooting drugs on sidewalks are all offenses against maintaining a civil society. Shellenberger drives home the point that a city will not remain civil unless its laws are enforced reliably and equally, regardless of who the lawbreakers may be.

Compassion, he argues, begins after an arrest for these misdeeds, not in place of it.

After an arrest, for example, he asserts that the schizophrenic refusing treatment should be involuntarily hospitalized and stabilized with what are now highly effective anti-psychotic medications. Once in their right mind, he writes that they should be given the choice between staying that way or risking more serious interventions with the criminal justice system.

The mentally ill often have family members who have desperately been trying to help. Shellenberger argues that a confrontation with the law should more often lead to a family obtaining a mental health conservatorship over their loved one. This strengthens the ability of the family to coerce compliance with treatment, often provides access to a home, protects the patient, and protects the rest of us from them.

Similarly, the book argues that the methamphetamine addict or other substance abuser should be forced to choose between treatment and abstinence or incarceration.

Local American Civil Liberties Union officials with “pathological altruism” and outsized power to pressure California policymakers make repeated appearances in the book. Purporting to be helping the homeless, these self-appointed guardians of civil liberties are a major impediment to the mentally ill receiving treatment.

Shellenberger asks the ACLU if a mentally ill lawbreaker should face “involuntary psychiatric treatment as an alternative to incarceration.” A representative of the group replies: “no matter how a person falls into homelessness, the root cause is always the scarcity of affordable housing.”

Note how the word “homeless” gets used as the answer to a question about “illness.”

It’s almost plausible to imagine the ACLU giving the same reply to a deliberately absurd question: “Do you think giving away housing cures bipolar disorder and schizophrenia?”

Shellenberger follows up with a more reasonable hypothetical, asking if a person who is arrested for repeated public defecation should be given a choice between treatment and incarceration. The ACLU representative responds: “I would favor the option of them not being arrested in the first place. That whole scenario is problematic.”

The ACLU supports conservatorships that allow relatives to care for the elderly with dementia. Yet when a 20-something son is refusing treatment for a medically manageable case of schizophrenia, the group is willing to risk letting the young man dangerously disappear onto the streets rather than give the family the power to intervene.

Shellenberger asked the ACLU why there isn’t a consistent position for both mental problems and was told the difference is that “psychiatric disabilities are more episodic and responsive to treatment” than dementia.

A reader begins to wonder: Is there any point where the civil libertarians think a civil society should provide treatment to a sick person who is unable to rationally approve it on his or her own?

Tough Love vs. “Pathological Altruism”

The book features interviews with representatives of social welfare nonprofits who insist on similarly baffling policies. Because they blame the existence of a street population on insufficient housing, rather than unaddressed mental health and drug addiction, these groups have a perverse hostility to the creation of homeless shelters.

Instead, they pressure policymakers to create permanent, personal residences, to house the homeless for the long term. This is the meaning behind deceptive code phrases such as “Housing First” and “Permanent Supportive Housing.”

But those who see the challenge as primarily mental health and substance abuse tell Shellenberger that giving away free housing just makes problems worse. Housing, they argue, must be used as a carrot to coerce personal improvement. It must be earned.

The proper bargain, they say, goes like this: We’ll provide basic shelter and get you off the street because that is the humanitarian thing to do. But if you want a place of your own, you’ll need to get treatment, maybe get a job, and, if possible, learn to take care of yourself.

This logical tough love approach is anathema to the “pathological altruism” movement and the politicians influenced by it.

One is San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, who crops up as another prominent chaos creator in San Fransicko. The adopted child of Weather Underground terrorists Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn, Boudin portrays himself as an advocate of criminal justice reform, but instead delivers criminal justice indifference.

Enhanced access to illegal narcotics is the last thing needed by a large and vulnerable population of street denizens. Shellenberger wrote that in 2020 “Boudin announced that he was not going to prosecute street-level drug dealers.” The ACLU supported this abdication of responsibility. Unsurprisingly, San Francisco ended up with a record number of overdose fatalities.

Although much of the book covers specific problems of San Francisco, Shellenberger shows these policy problems afflict California generally. More worrisome, he reminds readers that California trends have a way of migrating across the continent. Wherever you live, these problems may be coming your way.

In today’s San Francisco, the ACLU is working to prevent families from saving their loved ones from criminal jeopardy, terrible mental afflictions, substance abuse, and a much higher chance of dying young. The nonprofits supposedly “helping” the homeless seem to think giving away apartments is a cure for drug addiction and mental illness. And the top prosecutor allows gangsters to sell hard drugs with impunity to the most desperate people in his town.

The book’s title, San Fransicko, is a reference to all the people making these deranged decisions.

But it’s insufficient to call them crazy. They’re also mindlessly cruel.