Special Report

Margaret Sanger: The Birth of Birth Control

Margaret Sanger and her sister Ethyl Byrne, on the steps of a courthouse in Brooklyn, New York, on January 8, 1917. Source: Wikimedia. License: Public domain.

Margaret Sanger and her sister Ethyl Byrne, on the steps of a courthouse in Brooklyn, New York, on January 8, 1917. Source: Wikimedia. License: Public domain.

The Legacy of Margaret Sanger (full series)

The Birth of Birth Control | The Tragedy of Overpopulation

Back in the USSR | Sterilization | The Woman Who United the Left

Summary: The founder of the largest abortion provider in America is often remembered for her efforts to legalize contraception as well as her eugenicist views of the “fit” and “unfit.” Less remembered is the philosophy of Birth Control that she fostered by fusing together socialism, population control, and racial chauvinism. Much more than her role in advancing abortion “rights,” Margaret Sanger taught so-called Progressives how to unify leftist causes—a legacy still continued today and one that conservatives can’t afford to misunderstand.

Ed. note Feb. 14, 2022: Since this and other articles were published, Planned Parenthood has distanced itself from Sanger, with CEO Alexis McGill Johnson writing in 2021:

“Margaret Sanger’s racist alliances and belief in eugenics have caused irreparable damage to the health and lives of Black people, Indigenous people, people of color, people with disabilities, immigrants, and many others. Her alignment with the eugenics movement, rooted in white supremacy, is in direct opposition to our mission and belief that all people should have the right to determine their own future and decide, without coercion or judgement, whether and when to have children. . . . We denounce the history and legacy of anti-Blackness in gynecology and the reproductive rights movement, and the mistreatment that continues to this day.”

If you want to start a shooting war, praise Margaret Sanger before conservatives and lambaste her before liberals. Then watch the fireworks.

The woman who birthed Planned Parenthood—today the biggest provider of abortion services in the country—left a legacy so charged it’s bitterly despised by the Right and fanatically defended by the Left. A quick Google search on Margaret Sanger will likely to turn up two kinds of results: warped apologia painting the woman who infamously spoke before the Ku Klux Klan as a champion for black women and tirades against an arch-racist supposedly bent on the eradication of all non-whites. But neither of these pictures captures the more complicated woman and the legacy of political activism she left behind.

Why does that matter? Well, there’s no end of articles, TV segments, and books that try (and fail) to put Sanger in a single box. She’s been labeled a dupe for the Soviets, an avowed socialist, a white supremacist, and a committed eugenicist (“beautifying” humanity by controlling reproduction). She’s just as frivolously defended as a devoted feminist, a working-class champion, and—in Planned Parenthood’s words—a “complex and imperfect” woman of nevertheless “heroic accomplishments.”

But these characterizations capture only part of what Sanger espoused. A deeper examination requires scrutinizing “birth control,” a term that today only refers to contraceptives, but to Sanger was a philosophy.

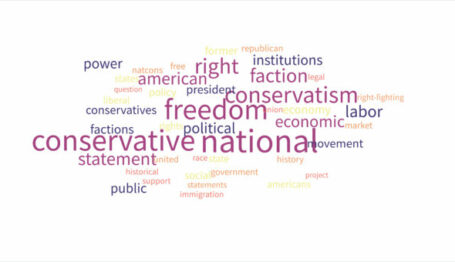

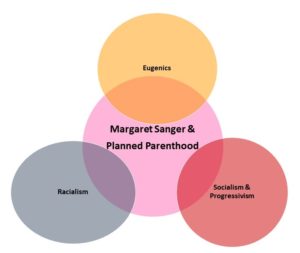

It’s that philosophy of capital-B, capital-C Birth Control that puts her squarely in the middle of three major pillars of 20th-century Progressivism: socialism, eugenics, and white supremacy—causes she drew together for her own political ends without adopting any one of them entirely. Sanger should be most remembered for laying the groundwork for the modern Left’s remarkable success in coalition building and political activism. She had a goal and worked with anyone to achieve it, a strategy her successors have adopted to great success.

That strategy really began with Lenin, who above all prized a final victory. He worked with whomever and did whatever was necessary to get there. To Lenin, a revolution is fought by the masses but led by a handful of elites who build their coalitions in secret—and never air their dirty laundry. As the scholar and ex-socialist Gary Saul Morson has put it, “The whole point of Leninism is that only a few people must understand what is going on.”

Sanger (whether she knew it or not) carried the strategy further. It’s evident in every election advertisement from the Left: The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) preaches global warming as zealously as the Sierra Club, while Greenpeace promotes labor rights and abortion on demand in the same breath. Why?

The modern Left advances all of its positions at once, or it advances none. And Sanger taught them that lesson.

Of course, to make common cause with misanthropes you must have something in common, and Sanger certainly did. Her Birth Control philosophy was perfectly at home in a crowd of socialists, eugenicists, or outright racists—causes it saw as distinct from itself yet basically related. Birth Control didn’t sniff at alliances with anti-human leftists.

More than anything, it’s that comfortable proximity to things that both the Right and (at least ostensibly) the Left loathe that’s the most damning aspect of Sanger’s legacy.

Figure 1. Margaret Sanger’s Planned Parenthood felt perfectly at home in a crowd of socialists, eugenicists, or racists—causes it saw itself as distinct from yet basically related to.

The Birth of Birth Control

Like other Progressive products, the philosophy of Birth Control is utopian. In her 1922 book Pivot of Civilization, Sanger envisioned a “terrestrial paradise,” which was “not burdened by the weight of dependent and delinquent classes, a total population of mature, intelligent, critical and expressive men and women.”

Life for them would be enriched, intensified and ennobled in a fashion it is difficult for us in our spiritual and physical squalor even to imagine. There would be a new renaissance of the arts and sciences. Awakened at last to the proximity of the treasures of life lying all about them, the children of that age would be inspired by a spirit of adventure and romance that would indeed produce a terrestrial paradise.

It’s reminiscent of the bliss imagined by Karl Marx when he wrote that communism “makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have a mind [to], without ever becoming [a] hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.”

If Sanger’s philosophy is utopian, she learned it from Marx. Like Progressivism, Birth Control isn’t Marxism, but it shows Marxist roots in its materialism, sense of class struggle, and disdain for Christianity. Everyday people are the source of society’s problems. Government is always the solution. And religion is a stumbling block to state action.

No doubt, Sanger’s cynicism traces back to her close proximity with radical socialism as a young girl. Her parents were Irish immigrants who came as children to Canada and then the United States in the mid-19th century to escape Ireland’s devastating Potato Famine. Her father, Michael Higgins, tried to enlist in the Union Army during the Civil War at the ripe age of 13. (The recruiters turned him down. A year and a half later, the 15-year-old Higgins joined the 12th New York Volunteer Cavalry as a drummer and saw combat.)

Margaret Louise Higgins was born in Corning, New York, in 1879. As the daughter of a craftsman who chiseled marble and granite for cemetery tombstones, Sanger grew up very poor. Her mother, Anne, conceived 18 times; only 11 babies survived childbirth. Margaret came sixth.

In her 1938 autobiography, she recalls her father’s fascination with phrenology, the pseudoscience of studying skull bumps and shapes to determine mental traits. It was a predecessor to eugenics. According to Sanger, he studied under leading phrenologist Orson Fowler, whose 1843 book Hereditary Descent theorized that African Americans had naturally poor verbal skills and coarse hair, which made them suitable for nursing children and waiting on tables. Sanger later wrote:

Father believed implicitly that the head was the sculptured expression of the soul. Straight or slanting eyes, a ridge between them, a turned-up nose, full lips, bulges in front of or behind the ears—all these traits had definite meaning for him. . . . One of Father’s phrases was, “Nature is the perfect sculptor; she is never wrong. If you seem to have made a mistake in reading, it is because you have not read correctly.”

Young college graduates often came to Higgins seeking career advice. He “examined their heads and faces,” Sanger wrote, and “told them where he thought their true vocations lay.” She later observed that “I could not help picking up his principles and some of his ardor, though I have never been able to analyze character so well.”

But it was Michael Higgins’ strong interest in women’s suffrage and social causes that probably had the biggest effect on his daughter’s politics. Sanger called him a socialist “who believed in the equality of the sexes . . . [and] fought for free libraries, free education, free books in the public schools, and freedom of the mind from dogma and cant.”

Sanger’s parents were Roman Catholics, but Michael Higgins later became an atheist. He “took up socialism because he believed it Christian philosophy put into practice” because “to me its ideals come nearest to carrying out what Christianity was supposed to do,” Sanger recalled in her autobiography.

In 1902, Margaret Higgins married William (originally Wilhelm) “Bill” Sanger, a German-born architect and artist who immigrated to the United States with his family in 1878. In 1906, the couple moved to Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, where William Sanger designed and built their house.

If Michael Higgins held to the relatively benign socialism of the late 19th century, Bill Sanger was a radical. The Sangers joined the newly formed Socialist Party of America, which supported the abolition of private property. In 1911, Bill Sanger ran (and lost) as the Socialist Party candidate for the New York City Board of Aldermen. He also helped organize the Syndicalist League of North America, a revolutionary labor group created by Marxist organizer William Z. Foster to “bore from within” the American Federation Labor (AFL) into supporting syndicalism, a form of union-based socialism.

Bill was well-connected to the who’s who of the early 20th-century American Left, introducing his wife to his personal friend and five-time Socialist Party of America presidential candidate Eugene Debs; John “Jack” Reed, who sympathetically documented the 1917 Russian Revolution; Communist Party USA chairwoman and American Civil Liberties Union co-founder Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, who died during a visit to the Soviet Union; communist Alexander Berkman; anarchist Emma Goldman; and William Dudley “Big Bill” Haywood, who founded Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a communist labor front.

She recounted that “our living room became a gathering place where liberals, anarchists, socialists, and IWW’s could meet,” mostly so they could trade ideas with Bill.

Margaret, however, was less committed to the socialist cause than her husband. “My own personal feelings drew me towards the individualist, anarchist philosophy,” she wrote in her autobiography. “It seemed to me necessary to approach the ideal by way of Socialism . . . . Therefore, I joined the Socialist Party.”

This was before the advent of Birth Control philosophy, when Sanger was still blending bits of leftist thought to form a larger ideology. Perhaps more influential in that process than socialism was her newfound atheism. Like her father, she was an iconoclast irritated by convention. “The whole sickly business of society today is a sham,” the young Sanger scribbled in her journal. Channeling Marx’s famous quip about “the opiate of the people,” she criticized “the vapid innocuities of religion” for drugging the working class into contentment. The founding statement of her 1914 magazine Woman Rebel was “No Gods, No Masters.”

Although she eventually dropped doctrinal Marxism, its coarse view of religion remained central to Margaret Sanger’s worldview. In time, she abandoned socialism altogether as unhelpful in achieving Birth Control’s final goals, yet socialist politics served as Sanger’s introduction to activism.

In the next installment of “The Legacy of Margaret Sanger,” learn about Sanger’s efforts in population control.