Deception & Misdirection

Lost causes

[Continuing our series on deception in politics and public policy.]

I was a child in Alabama at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. One day in 1961, a bus carrying Freedom Riders (people attempting to break the system of segregation in bus travel) was attacked and burned in an incident that started four blocks from my home; I discovered recently that the attack was planned in a meeting hall across the street from my home. The bus burning was so significant that its 50th anniversary was noted with programs on HBO and PBS and a show hosted by Oprah Winfrey.

I remember the day in 1963 on which four little girls were killed in a church bombing in Birmingham, about 60 miles to the west from my home town. That day, I witnessed, from across the street, a melee that broke out when local civil rights leaders, protesting segregation at the town library, were attacked by a mob and one of them was stabbed.

Back then, virtually all public officials in Alabama were Democrats. On rare occasions, Republicans would win a seat or two out of the 140 seats in the state legislature, or a Republican would win an office in a nonpartisan election such as for the city council, but the GOP was generally a nonentity in the state’s politics. As late as the beginning of my second semester in law school, there were zero Republicans in the legislature.

As the child of working-class parents in Alabama, I identified initially as a Democrat, but, as I grew older and began to think on my own, I identified increasingly with the few Republicans I saw around me. As a general rule, the Republicans were the better-educated people, the white-collar workers and professionals, and the Yankees and others who had moved to the South. They were the ones who represented progress toward racial equality. In my town, home of Fort McClellan, a number of those transplanted Republicans were retired from the military. One role model in this regard was General Edward Almond, who had served as Douglas MacArthur’s chief of staff and whose aide-de-camp in Korea was future Secretary of State Alexander Haig. When I was 13, I started reading William F. Buckley’s National Review magazine, and my identity was cemented as a “conservative libertarian Republican” (which is what the local paper called me in a profile published when I was 16).

A few years earlier, in the 1940s, there had been a movement, largely among college students from the South, to adopt the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of Southern identity, in defiance of the national culture that depicted Southerners as ignorant hicks, as rednecks/hillbillies/peckerwoods. It was a middle-finger to the privileged elites of the North, the folks who, in one famous phrase, were born on third base and thought they hit a triple. In 1948, when a breakaway faction of the Democratic Party, the States Rights Democrats, nominated Governor Strom Thurmond (D-South Carolina) for president, many of the young people supporting Thurmond waved the battle flag, which, up to that point, had fallen into disuse except for in memorials to relatives lost in the Civil War. Apparently for the first time, the flag became a symbol of defiance to the Civil Rights Movement. [Thurmond, it should be noted, later became a Republican. That fact is often used to tar all today’s Southern Republicans as racists. In fact, less than one percent of one percent of segregationist Democrats who held public office ever left the Democratic Party. Almost all Southern Democrat-to-GOP converts came from among so-called “racial moderates.”]

Six years later, in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (consolidating cases from Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and the federally controlled District of Columbia), school segregation by so-called “race” was declared unconstitutional. By the late 1950s and into the ’60s, the battle flag was used as a symbol of defiance by Democratic Party politicians, by the Ku Klux Klan (the Democratic Party’s terrorist arm), and, in general, by Southerners and lovers of rebellion.

(By the way, if you see an article that refers to the Confederate battle flag as the Stars and Bars, be aware that the writer is ignorant about the flag and too darn lazy to Google it. The Stars and Bars, once the official flag of the Confederate States of America, is a different flag, one that few people would recognize today. The Confederate battle flag, as we usually see it today, is a combination of elements from the flag of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and a similar naval flag.)

In the 1950s, many Southerners hung the battle flag in dorm rooms at Northern colleges or unfurled it at football games pitting Southern schools against Northern schools, or bought shot glasses or bikinis or postcards or license plates featuring the flag. (It wasn’t just the flag that served as a badge of Southernness. I remember college football games at which, after the announcer asked people to “stand for the national anthem,” the band would play “Dixie.” I remember politicians referring to the Civil War as “the War of Northern Aggression.” None of that was meant to be taken seriously.)

As in the case of the 1979-85 CBS TV show “The Dukes of Hazzard,” featuring a car named the General Lee with a battle flag design on the roof, there was, for millions of people, no intent to associate the flag with the oppression suffered by African-Americans under slavery and Jim Crow. To many, the flag was a symbol of Southern culture and of general rebellion against authority, something along the lines of the Guy Fawkes mask from the graphic novel and movie V for Vendetta, which is used by Occupy Wall Street types, anarchists, and libertarians who know little or nothing about 17th Century conflicts between Catholics and Protestants.

Even as some people used the flag to express nationalism and rebellion against authority, it was becoming a symbol of hate, used to show support for white supremacy and to intimidate supporters of the Civil Rights Movement. The Ku Klux Klan, originally a Southern organization, was reborn in the 1910s as a national group, powerful in non-Southern states like California and New Jersey. Only in the 1940s did Southern Klansmen begin to adopt the battle flag as one of their symbols. By the late 1950s, though, the association with the Klan was clear.

Segregationist politicians like Governor George Wallace (D-Alabama) and Ernest “Fritz” Hollings (D-South Carolina) raised the flag over their state Capitols, clearly as an expression of opposition to the Civil Rights Movement and the federal government. The Democratic Party owned that symbol. Wallace would lead a breakaway faction of the Democratic Party in 1968, briefly polling in second place in a three-way race for president and ending up with 13.1 percent of the vote. He would return to the Democratic fold and, as late as May 1972, was the biggest vote-getter in the race for the Democratic nomination, winning the Maryland and Michigan Democratic primaries and finishing the campaign less than two points behind the winner, George McGovern.

Jimmy Carter—a Wallace ally as the segregationist candidate for governor of Georgia in 1970—became the Democratic nominee for president in 1976 and 1980. Remember this?

In 1984, “Fritz” Hollings, the flag-raiser, ran for president, and was among the serious candidates for his party’s nomination. As far as I can tell from a search of the Nexis database of news articles, the role of Hollings in raising the Confederate battle flag over the state Capitol was never mentioned during the 1984 campaign.

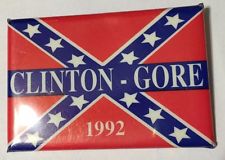

In 1992, the Democratic nominee for president was Bill Clinton, who, as governor of Arekansas, had continued the state’s longtime commemoration of the Confederacy, including Confederate Flag Day, and who had signed a designation of the central/top star in the state flag, above the name “Arkansas,” as representing the Confederate States of America. When Clinton ran for president—the protégé of a segregationist Senator (William Fulbright) whose running mate, Al Gore Jr., was the son of a segregationist Senator—we saw buttons like these:

Did I mention that the Alabama Democratic Party continued to use the white-rooster symbol of white supremacy as its emblem until 1996, and that the Kentucky Democratic Party does so to this very day?

(The Black Panther Party’s emblem was originally conceived as a parody of the Democrats’ white-supremacist rooster symbol. Really.)

What does this have to do with deception, the regular subject of this column?

One is that how the news media and political activists seized upon the display of the flag by Dylan Roof, the white-supremacist terrorist who murdered nine people during a church gathering in Charleston.

Roof was seen in photographs, discovered online, holding the Confederate battle flag and burning, trampling, and spitting on the U.S. flag. There is a document online that is supposedly his manifesto in which he denounces the U.S., including U.S. military veterans, although he exempts from his denunciation those who served in World War II or earlier. (I’m skeptical about Roof’s authorship of the so-called manifesto because the level of writing doesn’t seem to match his educational level, but the document appeared along with the pictures of Roof on a website that was supposedly registered in his name.)

At first, as usual in such cases, the media and the Left (but I repeat myself) tried to make the need for “gun control”—further restrictions on the legal ownership and use of firearms—the lesson of the horror in Charleston. That fell flat; it turned out that no “gun control” measure proposed by the President or his supporters would have made any difference in the case. But they never let a crisis go to waste, so the Confederate battle flag became the target.*

Not a single politician, it seems, called for punishing people who burn, trample on, or spit on the U.S. flag, because that’s not a priority of the Left.

None of the advocates of removing the battle flag have called for the elimination of T-shirts featuring gay-haters “Che” Guevara and Trayvon Martin. None of the advocates of removing the battle flag called for removing from places of honor the name of the vicious white-supremacist/Progressive Woodrow Wilson. For many Progressives, the real reason for getting rid of the flag is to eliminate a symbol that, to the Progs, represents (non-African-American) Southerners, whom they consider racially inferior to themselves and whom they blame disproportionately for opposition to the President.

The other aspect of deception is that the media somehow turned the Confederate battle flag—in particular, the one on the statehouse grounds in South Carolina—into, somehow, a problem for Republicans.

In 1962, Democrats raised the battle flag over the South Carolina Capitol. In 1997, a Republican, Governor David Beasley, removed it to a lesser location on the Capitol grounds, which Democrats exploited to beat him in the next election. In 2015, another Republican governor, Nikki Haley, an Indian-American woman, stood with Senator Tim Scott (R-South Carolina), an African-American, to announce her plan to remove the flag from the Capitol grounds entirely.

Yet it’s the Republicans’ problem. Because, you see, Republicans are the problem.

As for me, I recognize that some people see the battle flag as a symbol of honorable things. But, like the burning cross and the swastika and terms like “states’ rights,” the flag now carries the stench of evil, and it should go.

When I was eight years old, I resolved that I would never use the N-word. It was Alabama, 1965. Friends and family members thought it was a silly affectation and made fun of me for it. Later, I was called an N-word-lover for being a Republican; the theory was that any so-called “whites” who defected to the GOP—the party of Yankees and Lincoln—would split the “white” vote and “let the N-words take over.”

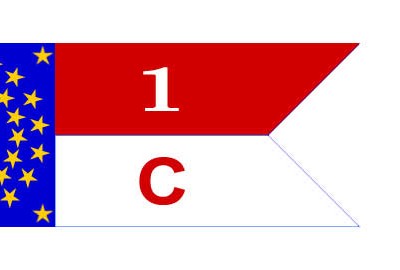

Yet I wanted to express my affection for Southern culture. Most people at that time would display the Confederate battle flag, but I understood even then that it was tainted forever. So I found a symbol that reaches back to the Civil War, that honors brave soldiers of the South, but that isn’t tainted.

That’s the flag of the First Alabama Volunteers, U.S. Cavalry—Southerners who fought for the Union. In my view, it’s time to take down the flag of one-party Democratic Party rule, and replace it with symbols of honor, like this one.

=========================

* Another piece of deception in the Dylan Roof case involved the attempt by some to discredit those who’ve reportedly fairly on the Trayvon Martin/George Zimmerman case, by associating their views with those of Roof. Apparently, Roof’s denunciation of the U.S. government and of U.S. veterans and his desecration of the U.S. flag don’t in any way discredit the views of those who share his views on those topics, but his display of the Confederate flag makes that symbol one that WalMart no longer allows on cakes. (Really: WalMart banned Confederate symbols from cakes. Per ABC News, “A man in Louisiana is asking for an explanation from WalMart after his request for a Confederate flag cake at one of its bakeries was rejected, but a design with the ISIS flag was accepted. Chuck Netzhammer said he ordered the image of the Confederate flag on a cake with the words, ‘Heritage Not Hate,’ on Thursday at a WalMart in Slidell, Louisiana. But the bakery denied his request, he said. At some point later, he ordered the image of the ISIS flag that represents the terrorist group. ‘I went back yesterday and managed to get an ISIS battleflag printed. ISIS happens to be somebody who we’re fighting against right now who are killing our men and boys overseas and are beheading Christians,’ Netzhammer said.”)

CBS News reported on Roof, the manifesto, and the Martin/Zimmerman case:

According to the manifesto, the Trayvon Martin case was a moment of transformation. Martin, an unarmed 17-year-old, was killed in a 2012 confrontation with neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman in a high-profile case that tested Florida’s “stand your ground” law. Zimmerman was acquitted, but the case became a lightning rod for a national protest movement now typified by the slogan “black lives matter.” Roof’s apparent searches for information led to extremist websites and a conclusion that “Zimmerman was in the right.”

The TV version of the CBS report was accompanied by a picture of Martin not as a 17-year-old but as a 12-year-old. (A key piece of the deception in the case of Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman turned Martin from an older teenager who attacked a Latino man in an apparent hate crime—he thought George Zimmerman was gay—into an innocent victim, indeed, a child.) The CBS report calls Martin “unarmed,” neglecting to mention that he was slamming Zimmerman’s head repeatedly into concrete; the CBS report claims a connection to Florida’s “stand your ground” law (it was not a factor, although it might have served as Martin’s defense if he had been tried for the deadly assault); and the CBS report claims that “Roof’s apparent searches for information led to extremist websites and a conclusion that ‘Zimmerman was in the right.’” Here’s what the manifesto said:

The event that truly awakened me was the Trayvon Martin case. I kept hearing and seeing his name, and eventually I decided to look him up. I read the Wikipedia article and right away I was unable to understand what the big deal was. It was obvious that Zimmerman was in the right.

Read that again. The “extremist websites” (as CBS News put it) that, according to the supposed manifesto, led Roof to the conclusion that Zimmerman was “in the right”?

Wikipedia.

Will someone please call the folks at Wikipedia and let them know that CBS News thinks they’re extremists?