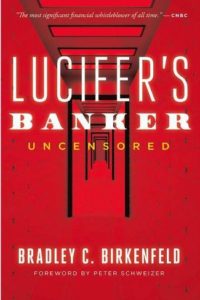

Book Profile

International Finance and Intrigue in Lucifer’s Banker Uncensored

Bradley C. Birkenfeld. Credit: C-SPAN.

Bradley C. Birkenfeld. Credit: C-SPAN.

Lucifer’s Banker Uncensored by Bradley C. Birkenfeld (Republic Book Sellers, 2020) is about power and corruption at the highest levels of what’s arguably the world’s most powerful institution—international finance—with Birkenfeld cast as the plucky rogue poised to take it all apart. The book even opens with a quotation from Wall Street villain Gordon Gekko trumpeting the virtues of greed.

“If you haven’t gotten the gist of me yet,” Birkenfeld writes, “I’m a hammer looking for nails.”

Lucifer’s Banker Uncensored reads like an Ian Fleming thriller, filled with intrigue, betrayal, and double-crossing government agents. So much so, at one point Birkenfeld compares his own luxurious life in Switzerland and America with that of the dashing British spy—beautiful Brazilian babe, expensive champagne, parachuting from airplanes, and all. Anyone who’s read a Tom Clancy novel will feel right at home with Birkenfeld’s no-nonsense, straight-talking style.

Birkenfeld was a master of money living large with the rich and famous, and he wants you to know it. But all that lucre dried up the minute he decided to expose a $25 billion tax fraud scheme hatched by UBS, one of the most powerful banks in the world. It even earned him the wrath—and a 30-month prison sentence—from the U.S. government.

Lucifer’s Banker originally debuted in October 2016 at the National Press Club in Washington, DC—and just barely. According to Birkenfeld, his tell-all true story incurred the wrath of powerful movers in business and derailed the book’s publication with major publishers. “I knew too much,” he writes. Facing the threat of lawsuits he published a censored copy of the book, what he recalls as “a bittersweet event,” but the desire to tell the whole truth only burned brighter.

Four years later, we have Lucifer’s Banker Uncensored.

Boston Beginnings

Birkenfeld’s tale begins in the late 1980s in Boston, where his struggle up the corporate ladder landed him in the currency department of a major pension-management firm handling some $30 billion in dozens of major currencies from around the globe. It was there he had his first colorful brush with corruption when his team was asked to make up a $750,000 loss by “padding” currency sales with undisclosed markups—a practice he calls “so illegal it would’ve made Tony Soprano blush.”

“From there,” he adds, “the snowball picked up more cow dung in its inexorable roll downhill.” The illegal practices included false pension profit reports to clients that concealed losses, mail and wire fraud, bribery, and even wiretapping clients by failing to disclose their phone calls with the firm were being recorded via Dictaphone. (Massachusetts is a two-party state when it comes to recording conversations).

When Birkenfeld brought the matter to the firm’s legal department and even its annual shareholder meeting, his reward was the unemployment line—a foreshadowing of his situation with UBS so many years later, FBI investigation and everything.

When that investigation dead-ended, he was left blackballed in the United States. Birkenfeld blames the failure on rampant corruption in the FBI’s Boston office, which was simultaneously taking bribes from the murderous gangster James “Whitey” Bulger” as it was investigating his case. So Birkenfeld turned to the global hub of banking: Switzerland.

Birkenfeld calls the country a “banker’s Disneyland” and little wonder. Private banking is practically ingrained in the national DNA, dating back to its days as a refuge for beleaguered Protestants in the 16th and 17th century Reformation. Swiss bankers offered simple money management services to the largely middle-class Reformed exiles from Roman Catholic France, and they grew more sophisticated with time. This complemented the Swiss cantons’ already famous policy of neutrality in foreign wars, eventually making Geneva the center of humanitarian groups such as the Red Cross and international treaties like the Geneva Conventions.

Eventually bank secrecy was even embedded in the national constitution in 1934, making it a criminal act for a banker to reveal details of a client’s account. This effectively rendered that invisible money virtually untaxable.

Birkenfeld recounts his capers wining and dining the ultra-wealthy into Swiss tax havens from Credit Suisse to Barclays and finally to UBS, the 15th-largest bank in Europe, with total assets of €782 billion ($926 billion). Seemingly overnight he became UBS’s highest-paid banker in Switzerland.

From there the book assumes a dizzying Wolf of Wall Street vibe: loose women, $25,000 watches, luxury cars sporting six-figure price tags, high-powered business negotiations in Wolfsburg Castle (“where Alexandre Dumas and Franz Liszt had once bedded down”), and even sipping Courvoisier with Osama bin Laden’s sister in a surreal (and heated) scene shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center.

Wolfsburg Castle. Credit: Axel Hindemith. License: Wikimedia.

Banker Turned Whistleblower

But 9/11 also put the squeeze on lucrative private banking. The PATRIOT Act and new regulations brought unprecedented scrutiny from the U.S. government on UBS, which, Birkenfeld writes, secretly produced a get-out-of-jail-free card for the firm, in which the firm would pin the blame for billions of dollars in hidden money on its star employees. These same star employees had made the company a fortune squirreling rich Americans’ cash away. If the feds came knocking, UBS could sell Birkenfeld down the river and get away scot-free.

So before jumping ship in late 2005 he set about quietly documenting UBS’s complicity in helping him violate its own secret rule barring employees from helping clients dodge U.S. tax regulations (much of it included in the book’s appendix). “It was time to become the scourge of every great financial institution,” he writes, “a pissed-off, dangerous internal whistleblower.”

To hear him tell it, the $20 billion tax evasion case that Birkenfeld eventually brought to the Justice Department was at least as motivated by guilt as indignation at UBS’s betrayal. After all, hadn’t he helped the “sneaky Swiss banking pirates” hide billions from Uncle Sam while regular Americans had to pay their taxes?

Hilariously, at one point in 2006 while shopping for law firms, Birkenfeld considered hiring Covington & Burling, where future attorney general Eric Holder was a partner and where the scandal-ridden Obama appointee would slink back to an office that was reportedly kept open for him for six years. Birkenfeld passed because UBS was a Covington & Burling client.

I won’t spoil the details, but what Birkenfeld found at the Justice Department can hardly be described as justice. He names names of the federal agents who should have welcomed a whistleblower cracking open a massive case of tax fraud committed against the U.S. government but didn’t, largely for reasons he ascribes to corruption and department politics. He also names the American account holders at UBS and the eye-popping size of their secret accounts, including famous actors, businessmen, and politicians. Suffice it to say Eric Holder, Hillary Clinton (including the Clinton Foundation), John Kerry, and other members of the Obama administration feature heavily in the cover-up.

Thanks to Birkenfeld’s testimony, UBS was ultimately forced to turn over the names of 4,500 Americans with secret accounts in April 2009 (although Birkenfeld points out that, out of its 19,000 U.S. account-holders, that list was “cherry-picked”), leading to recovered assets and fines worth a stunning $25 billion.

Less than six months later Birkenfeld was sentenced to three years in prison for failing—according to the government—to disclose his personal involvement in the UBS tax evasion scandal when he came forward as a whistleblower. (Birkenfeld maintains that he was up-front about his role at UBS from the start.)

Cover-up Revealed

The story has a happy ending, however. Birkenfeld was released in August 2012, around the time the Justice Department’s cover-up was revealed—largely thanks to a watchdog group, the National Whistleblower Center in Washington, DC. As a whistleblower, the IRS awarded him $104 million (less taxes), and Birkenfeld took his new book to town, exposing UBS’s scheme across Europe and Canada.

As Lucifer’s Banker Uncensored closes, he even mulls over the idea of starting his own “whistleblower headquarters” to deliver justice where it’s needed. The name: Hammer, Inc.