Foundation Watch

Foundation Adrift: The Aimlessness of the Annie E. Casey Foundation

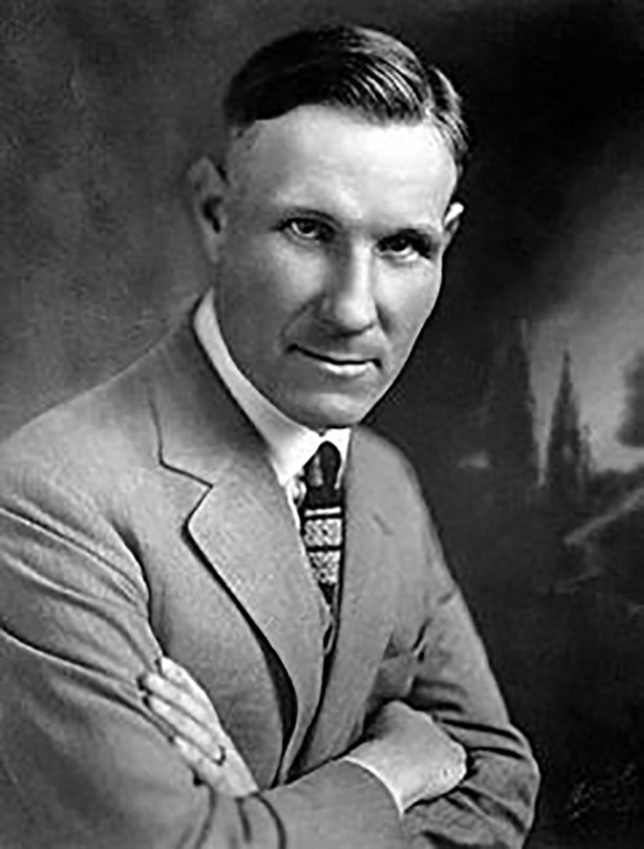

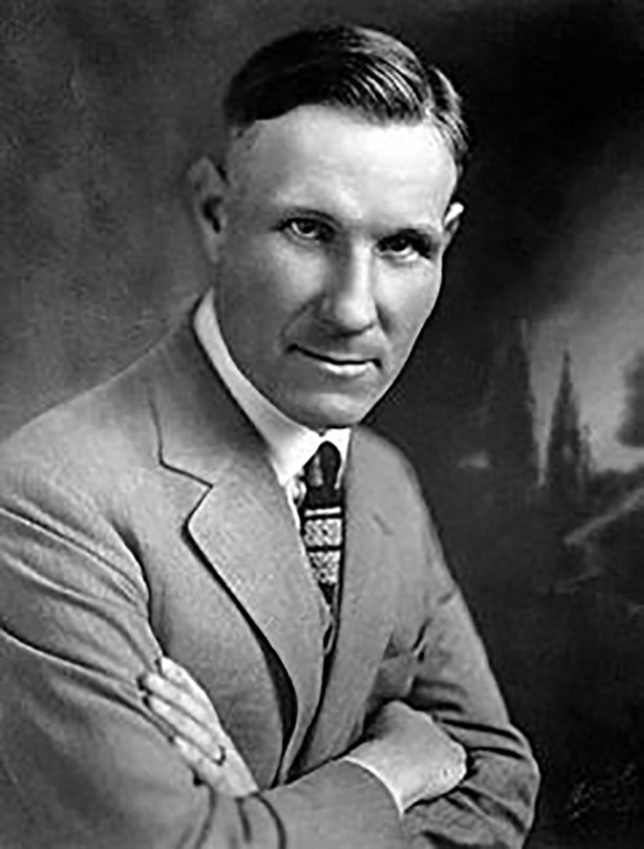

Some individuals who knew James E. Casey argue that he wouldn't recognize the agenda of today's Annie E. Casey Foundation. But the problems begin with the fact that Mr. Casey was a tight-lipped donor who kept most of the motivations for giving to himself. Thus, his views of philanthropy, other than a general desire to help children, remain unprovable. Credit: USDOL. License: https://bit.ly/2k4vx8a.

Some individuals who knew James E. Casey argue that he wouldn't recognize the agenda of today's Annie E. Casey Foundation. But the problems begin with the fact that Mr. Casey was a tight-lipped donor who kept most of the motivations for giving to himself. Thus, his views of philanthropy, other than a general desire to help children, remain unprovable. Credit: USDOL. License: https://bit.ly/2k4vx8a.

Foundation Adrift (full series)

The Aimlessness of the Annie E. Casey Foundation | The History of Casey’s Philanthropy | The Casey Foundation Today | The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Future

Summary: The Annie E. Casey Foundation influences much about how American policymakers think about child welfare. However, the policies promoted by the foundation leave many friends and colleagues of founder James E. Casey scratching their heads, wondering if the humble businessman would approve of the work his legacy now supports. Despite entrusting his foundation to employees of his company, which would theoretically establish a consistent culture for the Annie E. Casey Foundation, some feel it was not enough to protect Mr. Casey’s legacy from the philanthropic sector’s strong leftward drift.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation is America’s 30th-largest foundation, with assets in 2015 of $2.6 billion and grants of $118 million according to the Foundation Center. Its size makes it slightly smaller than the foundations created by Conrad Hilton and James Simons and slightly larger than the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, the largest foundation created from the wealth of Warren Buffett.

James E. Casey, the founder of United Parcel Service, and his family created the foundation in 1948. When Casey died in 1983, the foundation received the majority of his estate; a smaller portion went to Casey Family programs. The foundation’s endowment doubled in 1999 when United Parcel Service raised $5.47 billion from the largest initial public offering of the 20th century.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation specializes in programs that deal with children. It publishes Kids Count, an annual statistical reference that is widely cited by the media when they write about children. It also funds fellowships for journalists who write about children and families. It is the largest funder of research about children and families, and as such has a heavy hand in the debate about public policies towards children. In particular, it has called, throughout its history, for children to remain with their parents as long as possible, even if the parents are abusive.

Although funding programs for families and juvenile justice is the majority of what the Casey Foundation does, it is also one of the two largest foundations in Baltimore, awarding millions in grants each year to nonprofits in that city. The foundation, collaborating with Johns Hopkins and the city of Baltimore, has been a partner in East Baltimore Development Inc., a project that existed since 2003 and that will not be completed in the near future. In 2016, the Casey Foundation launched Pittsburgh Yards, a development in Atlanta, where United Parcel Service has its headquarters.

The Casey Foundation also has its hand in areas that have little to do with social policy. Pick up a copy of Washington Monthly, the venerable liberal political magazine, and you’ll find the publication has two official sponsors: the Casey and Gates Foundations. It’s not clear what the Casey Foundation’s sponsorship of the magazine entails or whether the foundation has any influence over the magazine’s content.

Had Hillary Clinton won the 2016 presidential race, the Annie E. Casey Foundation might have been a major player, as Sen. Tim Kaine’s wife, Anne Holton, was a consultant for the foundation for several years and won the foundation’s life achievement award in 2014. (Instead of being Second Lady, Holton in 2019 was named interim president of George Mason University.)

The Casey Foundation originally focused its giving on programs to help orphans and other disadvantaged children, but it has become steadily more radical. Looking at its 2015, 2016, and 2017 IRS filings, one sees grants to such hard-left organizations as the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Institute for Policy Studies, and the Alliance for Justice, as well as $4,965,000 in grants and $925,000 in program-related investments to the Tides Foundation, the leading pass-through nonprofit for the Left, as well as $6,713,000 for its spinoff, the Tides Center. In addition, the Casey Foundation has hired Fenton Communications, the go-to public relations shop for America’s radicals, which has gotten contracts of $820,000 in 2016 and $1,090,000 in 2017.

The story of the Annie E. Casey Foundation is one about the consequences of donor silence. Some individuals who knew James E. Casey argue that he wouldn’t recognize the agenda of today’s Annie E. Casey Foundation. But the problems in determining whether the agenda of today’s Annie E. Casey Foundation has drifted from its donor’s intent begin with the fact that Mr. Casey was a tight-lipped donor who kept most of his motivations for giving to himself. Thus, his views of his philanthropy, other than a general desire to help children, remain unknown.

Who was Jim Casey?

James E. Casey (1888-1983) was one of the greatest entrepreneurs of the 20th century. Casey’s father tried to be a success in the 1898 gold rush, but he returned from the Yukon with no gold and in poor health. Just before his death in 1902, he told his teenage son, “Jim, you want to be a businessman. Never work with your hands.”

Casey followed his father’s advice and in 1907 started the American Messenger Company in Seattle, in which a corps of bicycle messengers delivered messages and packages in the Seattle area. Interviewed in the Saturday Evening Post in 1953, Casey couldn’t remember the other messengers’ names, but he remembered their nicknames: the Klondike veteran nicknamed “Frozen Feet,” and a guy nicknamed “the Paper Grinder” for the many ways he managed to get his clothes caught in the chains of his bicycle.

In 1913, the American Messenger Company changed its name to Merchants Delivery Service to reflect its shift to a package delivery company. Motorcycles replaced the bicycles. In 1919, the name changed for a third time to United Parcel Service. The company’s founders went through the Yellow Pages looking at possible names, and when they got to “United Fruit” James Casey’s brother, George, said, “That’s the name right there. United.”

The founders decided to add “parcel” to their name because they were in the business of delivering packages, and “service” because, in the words of founder Charlie Soderstrom, “we are a service organization with nothing to sell but service. Service should be in our name.”

Soderstrom is also responsible for another of UPS’s distinctive features: the brown color of its trucks. Jim Casey wanted yellow to be the company color, but Soderstrom successfully argued that painting the trucks the color of Pullman railroad cars would make the trucks easier to clean. Ever since then, the company has been nicknamed “Big Brown.”

UPS began as a package delivery service for department stores, first in Seattle, then Oakland, and then in New York City. The company attracted business by convincing department stores that having UPS deliver packages was more efficient than having the stores do it themselves. UPS spent a great deal of time figuring out the most efficient way to deliver packages. (Among their discoveries: it was easier to deliver 40 packages to 40 homes than 40 packages in one apartment building, because of the time it took to go up and down elevators.)

An article in Fortune in 1942 explained that UPS drivers were supposed to be, in the words of UPS’s official Manual of Instruction, “Businesslike Gentlemen.” The drivers, Fortune noted,

must shave daily, button their jackets fully, wear their caps straight on their heads. They must not smoke or chew in the vicinity of a customer, scuffle or engage in loud talk, whistle or yell at people. In collecting packages from the stores they are enjoined, “When making a pickup, conduct yourself as a gentleman.”

Fortune noted that another reason department stores contracted out their delivery services to UPS was the issue of unions. For a century, UPS has been a union shop, with its employees being members of the Teamsters. In April of this year, UPS signed its most recent five-year pact with the Teamsters, extending the union’s representation of UPS employees until 2023. The department stores, Fortune noted, “were glad to let somebody else deal with the tough and tenacious Teamsters Union.”

When World War II began, United Parcel Service was a department-store delivery service with operations limited to the West Coast, New York, Philadelphia, and a few Midwestern cities. After World War II, department stores began to move to the suburbs and customers began picking up their purchases at stores and putting them in cars. Given this change, in 1953 UPS became a “common carrier,” which could pick up packages from any location and deliver them to another location. By 1975, UPS could deliver packages to any part of the country, either by ground or by air.

As UPS grew, some aspects of its corporate culture remained constant. All UPS managers were also partial owners of the company, whose shares increased in value as the company prospered. (In the 1990s, UPS opened up stock ownership to drivers as well.) UPS regularly promoted from within; the board of directors and the CEOs after James Casey prided themselves on working their way up “from the truck.”

UPS was a large, privately held company that strived to tell the public—and its competitors—that it was much smaller than it actually was. “We have made no secret of our policies, but have believed it inadvisable to broadcast all our business affairs to the world,” James E. Casey announced at a 1957 conference celebrating UPS’s 50th anniversary. “We have kept confidential facts and figures pretty close to ourselves, as most prudent people do with their private affairs. In building this privately held company for the benefit of all of us, we have found that it pays to mind our own business and keep on sawing wood.”

UPS’s low-key strategy was a reflection of its founder. James E. Casey headed UPS for 55 years, but he strived to be as quiet and unassuming as he could.

Jack Rogers joined UPS in 1957 after he was graduated from Miami University in Ohio. He worked his way up and served as UPS’s CEO between 1984 and 1989. In an interview, Rogers said he first met Casey in 1966. Casey, Rogers recalled, “wouldn’t go out of his way” to call attention to himself. “He was a very subdued type of personality. He didn’t want the spotlight shined on him.”

Casey’s self-effacing character extended to his relations with the press. He only gave four interviews in his very long life: one to the New York Times, one to the Saturday Evening Post, and two to the New Yorker. “I do not like writers,” Casey told the Saturday Evening Post in 1953. “They phony things up.”

In 1947, Casey provided a short account of the origins of UPS to New Yorker writer Philip Hamburger. He explained to Hamburger that he wrote this short autobiography with great reluctance. “I am afraid to tell you something about myself,” he wrote, “because you will put it in the paper.”

Because Casey was so tight-lipped, much about him remains unknown. It is not known if he was a Democrat or a Republican, and his political donations, if there were any, remain secret. The chief primary source for James Casey’s writing is Our Partnership Legacy, a memorial volume of Casey’s speeches issued by UPS in 1985. The book has many anecdotes from UPS employees about the founder’s kindness, generosity, and decency.

It says nothing about Casey’s charity.

In the next installment of Foundation Adrift, learn about the history of Jim Casey’s philanthropy.