Green Watch

Climate Change Regulations in Pennsylvania: Carbon Taxes and Constitutional Questions

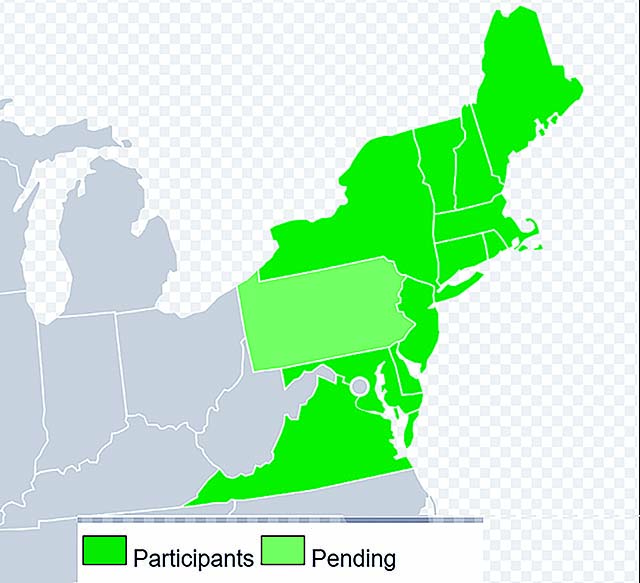

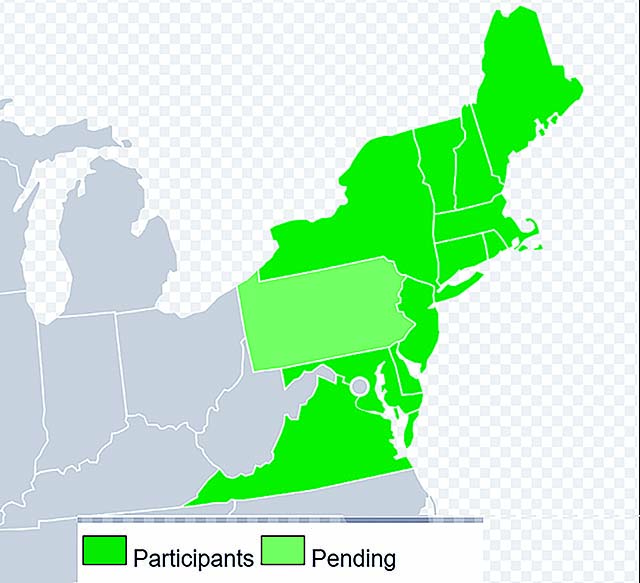

The RGGI agreement currently includes Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia. Credit: Cg-realms. License: https://bit.ly/3zj33c6.

The RGGI agreement currently includes Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia. Credit: Cg-realms. License: https://bit.ly/3zj33c6.

The Fight over Climate Change Regulations in Pennsylvania (full series)

No Discernable Benefits | Disputing the Official Findings and Data

Green Activism | Carbon Taxes and Constitutional Questions

Carbon Taxes and Constitutional Questions

But the EQB will not be the final word on RGGI. In fact, the day after the EQB approved cap and trade regulations, the state senate by a veto proof margin passed legislation that would prohibit Wolf from joining RGGI without legislative approval. Six of Wolf’s own Democrats voted to pass the legislation blocking unilateral executive action. The House is expected to vote on a similar bill when it reconvenes in late September. That’s not all. On September 1, the Independent Regulatory Review Commission (IRRC), an independent state agency that reviews regulatory proposals, approved the states entry into RGGI. The commission had previously recommended the EQB delay implementing RGGI in response to lawmakers’ and other stakeholders’ concerns about RGGI’s impact and legal concerns about the governor’s authority to act without a vote in the General Assembly.

The commission’s role is to determine whether a regulation is in the public interest, and to accomplish this end, the commission applies specific criteria spelled out in Pennsylvania’s Regulatory Review Act, which addresses the statutory authority of the agency, economic impact, and reasonableness.

The agency must review and respond to those comments in preparing its final regulation, usually making changes based on the comments in the final version of the rulemaking. At the final state of the process, the IRCC and the legislative standing committees in the General Assembly vote to approve or disapprove the final form of the regulation. This is an up-or-down vote on the entire regulation: The commission cannot approve some parts and reject others.

“If a regulation is approved by IRRC and the standing committees (or if the committees do not take any action) the agency can proceed to implement the regulation after a final review by the Office of Attorney General,” David Sumner, executive director of the IRCC explained in an email. “If IRRC disapproves the regulation, the commission will issue an order stating the criteria of the Regulatory Review Act which have not been met. The agency may then resubmit the regulation (possibly with revisions based on IRRC’s order) for reconsideration.”

Another negative IRRC recommendation against RGGI would have come just a few weeks before the House is set to vote on its own version of a bill requiring the legislature to approve any new regulations that enroll Pennsylvania into the multistate greenhouse gas initiative. the future of RGGI and its ability to expand could reach a critical turning point in September. The agreement currently includes Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia. State regulators set a cap on CO2 emissions in participating states from electric power generators and then require power plants in the RGGI states to purchase a credit or “allowance” for each ton of CO2 they emit.

Lawmakers who oppose Pennsylvania’s involvement with RGGI have argued that the “cap and trade” arrangements and quarterly auctions that figure into the multistate initiative would impose carbon taxes on state residents that only the state legislature has the authority to approve. Anthony Holtzman, an attorney with K&L Gates in Harrisburg, explained where carbon taxes come into play during his testimony before the Pennsylvania House in July 2020. He also told lawmakers that Pennsylvania’s constitutional and statutory laws do not give the executive the authority to sign or implement a multistate compact or agreement like RGGI.

“Because the Pennsylvania Constitution does not provide the governor or any other executive department official or entity with the power to enter into interstate compacts or agreements, the General Assembly alone possesses that power,” Holtzman said. The Harrisburg attorney also spoke at length on the tax question:

Our Supreme Court has long held that, under the Pennsylvania Constitution, the power to impose a tax is vested solely in the General Assembly. Under prevailing Pennsylvania case law, something qualifies as a ‘tax’ if it is a ‘revenue-producing measure.’ Regulatory ‘fees,’ by contrast, are merely ‘intended to cover the cost of administering a regulatory scheme.’ And therefore, as Pennsylvania’s courts have explained, whether an income-producing mechanism imposes a ‘tax’ or a ‘fee’ turns on the volume of income that the mechanism generates and the proportion of the income that goes to cover the program’s administrative costs.

Holtzman continued:

Under this standard, RGGI’s quarterly auction mechanism—which is the heart of the program—would qualify as a ‘tax,’ not a ‘fee,’ because the proceeds of the auctions are grossly disproportionate to the costs of administering the program. Through 2017, in fact, the RGGI signatory states had directed less than 6% of the proceeds toward the program’s administration. RGGI’s auction mechanism is designed to raise substantial sums of revenue—in fact, it has raised more than $3 billion to date—and the signatory states have used the vast majority of this revenue to either support policy initiatives (such as energy efficiency and renewable energy initiatives) or bolster state coffers through transfers to general funds. The auction program therefore imposes a tax that only the General Assembly can impose.

With an open U.S. Senate seat and a gubernatorial election next year, Pennsylvania’s political importance is difficult to overstate and hard to predict. But the battle over RGGI provides some insight into what might go down in upcoming statewide races and local races. While Wolf takes marching orders from green activists, it’s apparent that more than a few Democrats in the state legislature remain more aligned with their traditional benefactors in organized labor. This is particularly true of Democrats who reside in areas where the coal industry and the natural gas industry will take a direct hit from RGGI. In the end, the broad cross section of Pennsylvania residents who are part of Power Pa Jobs Alliance, which includes labor and business representatives may be the one that carries the day. In a press release that challenges Wolf’s “scheme to circumvent the General Assembly, and the Pennsylvania Constitution,” while also expressing support for legislation that takes aim at the “unconstitutional RGGI tax,” the alliance highlights some disturbing figures.

RGGI is a massive tax on two-thirds of Pennsylvania’s current electric generation plants. It will trigger the immediate closure of all Pennsylvania coal fired generation plants and many older natural gas plants. This includes plants that are capable of running for many years, including many plants that recently committed to provide power through June 2023. …

RGGI will also preclude the construction of any new natural gas fired electric generation plants within the Commonwealth that could otherwise replace lost generation from the closure of older fossil fuel plants.

The message elected officials and their constituents in organized labor in business harkens back to the founding period and goes something like “No Taxation, Without Representation.” If Wolf wants to scuttle the energy industry at the behest of green activists who invoke faulty scientific data, it looks more and more everyday like he’ll need to persuade a majority of House and Senate members to take a straight up-or-down vote in favor of new climate change regulations. Taxation with representation heading into the mid-term election cycle seems a tall order even for members of Wolf’s own party.