Foundation Watch

“Gaddafi Reloaded,” by Eliza Gheorghe

A Capital Research Center Highlight

August 30, 2007

Gaddafi Reloaded

How a Terrorist Financier Uses Charities for a PR Facelift

By Eliza Gheorghe

Summary: Westerners know that Libya is an authoritarian state with an abysmal human rights record. Yet Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi has signed on to the U.S.-led Global War on Terror, and he is promoting his son’s charitable foundation to increase his influence and refurbish his reputation abroad. What will come of these image-shaping efforts at “public diplomacy”?

Last week the State Department announced that Condoleezza Rice will visit Libya –probably in late October— becoming the first U.S.secretary of state to visit that North African nation since 1953. Rice will meet with Muammar Gaddafi, the erratic Libyan dictator whom President Ronald Reagan called “the mad dog of the Middle East.” It is expected that Rice will discuss ways to fight terrorism and expandU.S. trade and investment with a country the U.S. once treated as an enemy.

In recent years Libya has been refurbishing its reputation step by step. In 2003 it agreed to pay restitution to the families of the victims of the 1988 bombing of a Pan Am flight over Lockerbie, Scotland. After the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2004, Libya announced that it would surrender its nuclear materials and renounce its weapons of mass destruction program. That set the stage for Rice to announce in 2006 that the U.S. would resume diplomatic relations with Libya and remove that country from the State Department’s list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Gaddafi is undertaking an extreme image makeover. The longtime international pariah has emerged as a defender of innocent Bulgarian nurses and a vital U.S. ally in the Global War on Terror. He hands out humanitarian prizes and is launching charitable initiatives to help poor people around the world. This use of public diplomacy (or “soft power” as it is sometimes known) is one aspect of Gaddafi’s determined public relations effort to improve his personal image and his country’s international standing.

Charity and philanthropy play an important role in this quest for redemption. Nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs, enjoy high status around the world because they claim to be non-partisan and independent of governments; often they hold themselves out as the true representatives of civil society. Gaddafi well understands how to use them to promote Libya’s interests.

After a long period of diplomatic and economic isolation, Gaddafi has begun to get less hostile media coverage. He is frequently in the headlines in newspapers in Western Europe and scored a public relations coup in July when he claimed the initiative in resolving the Bulgarian nurses affair. This was the prelude to the July 25 visit by French President Nicolas Sarkozy to Tripoli welcoming Libya back into the embrace of the international community. Sarkozy was apparently the key to the release of the five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor imprisoned for eight years following a political show trial that convicted them of infecting more than 400 Libyan children with HIV.

The meeting of Sarkozy and Gaddafi produced statements of broad agreement to improve relations between Europe and Libya. More importantly, Gaddafi agreed to let France build a nuclear reactor inLibya intended to desalinate seawater. A bit later the French defense ministry announced that Libya would buy anti-tank missiles and a radio communications system from France in a $405 million deal.

While most Western observers know that Libya’s government is repressive and its human rights record abysmal, few are currently calling on Gaddafi to account for his past actions. The prospects for renewed trade and investment produce little incentive to ask questions about the blood money Libya has used to pay the victims of its terrorist attacks. Financial reports for Gaddafi’s charities and foundations are nowhere to be found. But Gaddafi’s self-serving global philanthropy is sure to become more generous as Libya opens itself to vastly increased Western foreign investment.

Gaddafi, Tyrant and Terrorist

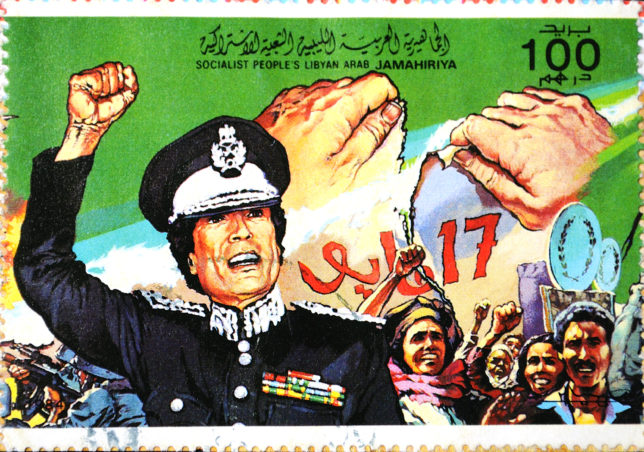

Since overthrowing King Idris I in 1969, Muammar Gaddafi has ruledLibya with an iron hand. Officially known as the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (“state of the masses” in Arabic, or perhaps, People’s Republic), the Islamic socialist state has sent assassination squads abroad to murder disaffected expatriates and for decades has imprisoned and killed dissenters at home.

Gaddafi began funding international terrorism in the 1970s. He reportedly contributed to the Black September Movement, which in 1972 murdered 11 Israeli athletes at the summer Olympic games inMunich. He had ties to the now-imprisoned Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, the legendary radical left-wing terrorist also known as Carlos the Jackal. The United States accused Gaddafi of masterminding the 1986 La Belle discotheque bombing in Berlin, (West) Germany, that killed three people and wounded more than 200, many of them U.S.servicemen. And the Libyan regime acknowledged involvement in the 1988 plane bombing over Lockerbie, Scotland, when it agreed to pay $2.7 billion to the families of the 270 people killed.

In 1982 the U.S. responded to Libyan terrorism by banning Libyan oil imports and the export to Libya of U.S. oil industry technology. Two U.S. Navy F-14s also shot down two Libyan fighters that fired on them over the Gulf of Sidra, over which Libya had claimed jurisdiction. In 1986 President Reagan ordered U.S. forces to attack Libyan vessels and bomb Tripoli and Benghazi in retaliation for the Berlin disco bombing. In one of the bombing raids, a girl claimed by Gaddafi to be his adopted daughter was killed.

Gaddafi became more cautious in his dealings with terrorists after 1986, but the Libyan leader still longed for revenge. While he funded various Islamic terrorist groups, he was careful to ensure that terrorists trained with Libyan money were not trained on Libyan soil. In 2000, Gaddafi asked Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe to receive Ayman Zawahiri, leader of Egyptian Islamic Jihad and Osama bin Laden’s deputy. Mugabe’s past willingness to shelter members of Islamic Jihad convinced Gaddafi that Zimbabwe might be “willing to host wanted Arab terrorists,” writes R.W. Johnson, president of South Africa’s Helen Suzman Institute, in the National Interest (Spring 2004).Zimbabwe had modern communications and banking facilities and it was conveniently close to Nairobi, Durban, and Cape Town, where Bin Laden had previously established terrorist cells.

Just 10 days before the September 11 attacks, Gaddafi gave a speech in Tripoli in which he openly boasted of al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden’s prowess and mocked the United States for failing to catch the terrorist leader after the East Africa embassy bombings in 1998:

“We no longer wage war with the old weapons. Now they can fight you with electrons and viruses. The crazy world powers that have invested huge amounts of money in weapons of mass destruction have found themselves unable to fight the new strain of rebellion. As a simple example, the U.S.A. is unable to fight someone called Osama bin Laden. He is a tiny man, weighing no more than 50 [kilograms]. He has only a Kalashnikov rifle in his hands. He doesn’t even wear a military uniform. He wears a jalabiyah and turban and lives in a cavern, eating stale bread. He has driven the U.S.A. crazy, more than the former Soviet Union did. Can you imagine that?”

Yet Gaddafi soon distanced himself from such harsh anti-American rhetoric, and Western media outlets began to report that he was denouncing al-Qaeda. After the U.S.-led toppling of Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, the shift became even more pronounced. Gaddafi allowed U.N. teams to inspect his nuclear facilities and agreed to dismantle his weapons of mass destruction program. Gaddafi even endorsed President George W. Bush’s Global War on Terror and acknowledged the right of the U.S. to defend itself from terrorism.

It seems apparent that Gaddafi recalculated the odds and decided that it was best to be in the West’s good graces—at least for the time being. But how Gaddafi intends to project his new image as a Westernizer and humanitarian is less clear.

Gaddafi, Humanitarian and Benefactor

Gaddafi’s efforts to improve his international image pre-date his criticisms of terrorism. In the late 1980s he gave $10 million to create a foundation in Switzerland that would administer the Al-Gaddafi International Prize for Human Rights. Time magazine reported (May 8, 1989) that the $250,000 annual award had “a surreal and oxymoronic ring” because Gaddafi was “better known as a patron of terrorism than a benefactor of humanitarian causes.”

In 1989 the inaugural prize went to South African president NelsonMandela, a hero to many in the Western world. But its subsequent recipients are less well-regarded: The list includes Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan (1996), Fidel Castro (1998), and in 2002 a group of 13 writers including the prominent French philosopher Roger Garaudy, a Communist-turned-Muslim.(In 1998 a French court found Garaudy guilty of denying the Holocaust and fined him the equivalent of $20,000. The government of Iran paid part of his fine.) The prize winner in 2004 was Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chavez, and in 2005 the prize went to Mahathir bin Mohamad, the anti-Western former prime minister of Malaysia. Interestingly, no prize was announced in 2006 or 2007 (to date), as Libya turns to the West.

Increasingly, whenever Gaddafi wants to send a message to the world he relies on 35-year-old Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi, his eldest son by his current wife. The younger Gaddafi, thought to be his heir apparent, is founder and head of the Gaddafi International Foundation for Charity Association, since renamed the Gaddafi Development Foundation(GDF). It has become one of the most visible charities in North Africa.

Saif al-Islam claims to represent “the voice of civil society.” In a recent Newsweek interview (August 13) he put it this way:

“If you are an active member in the Libyan civil society, you can criticize the government because you’re not a part of it. Sometimes you work with the government, sometimes not. And this gives you this margin of flexibility, because I’m not an official. In another capacity, I’m the son of the leader, and in that capacity I do business with the rest of the world. I have different hats.”

Right.

GDF has headquarters in Tripoli and Geneva, Switzerland, with branches in Khartoum, Berlin, Manila, Niamey (Niger) and N’djamena (Chad). There is a certain political logic to this. GDF’s charitable offices are in countries like Germany whose citizens have suffered at the hands of Libyan terrorists.

- The office in the Sudan, for instance, assists the regime of Moar Bashir, perpetrator of the Darfur genocide, who came to power in 1986 with Gaddafi’s support. Libya champions Sudan’s right to be free of Western interference in Darfur. (See Libya’s Foreign Policy in North Africa, by Mary-Jane Deeb, Boulder San Francisco and Oxford, Westview Press, 1991.)

- The GDF office in the Philippines assisted Saif al-Islam when he negotiated ransom payments to secure the release of Western hostages taken by the Islamic terror group Abu Sayyaf. GDF’s Philippine development aid program focuses on Mindanao, a region whose population is 20% Muslim.

- Chad and Niger are countries neighboring Libya that Gaddafi has long sought power over. To provide them with humanitarian and financial aid GDF sponsors an ominous-sounding Brothers of the South Society.

GDF’s proudest humanitarian achievement was the negotiation of the$2.7 billion deal compensating victims of the 1988 bombing of the U.S. airliner over Lockerbie, Scotland, that was engineered by Libyan agents. Gaddafi’s son denies that Libya was responsible for the atrocity, but in 2002 he offered to have his foundation compensate the relatives of those killed in return for lifting U.S. sanctions on Libya. This August he openly admitted that the release of the Bulgarian nurses was meant to pressure the British government to release a Libyan secret agent imprisoned for the Lockerbie bombing. Clearly Libya’s decision to apologize for the bombing is little more than a cynical long-term investment calculated to establish potentially lucrative trade relations with the West, particularly with the United States.

More information about the younger Gaddafi and his foundations comes from a 2002 British libel suit that Saif al-Islam launched against the London Daily Telegraph after the newspaper alleged in 1995 that he had engaged in international money-laundering. (He later dropped the suit after the newspaper apologized for calling him ”an untrustworthy maverick.”) An expert witness on Libya, Dr. Mansour O. El-Kikhia, a political science professor at the University of Texas, San Antonio, was called to refute Saif al-Islam’s claims to be a civil society leader. El-Kikhia testified that Saif al-Islam was no representative of civil society because Libya has no civil society capable of standing apart from the Gaddafi dictatorship.

El-Kikhia further testified that Gaddafi’s son used his “charities” to promote Libya’s foreign policy goals and he speculated about how they were funded. He scoffed at Saif al-Islam’s claim that the Gaddafi Development Foundation compensated the Lockerbie victims from a privately financed “fund for the victims of terrorism.” GDF was no more than a government office pretending to be a private charity.

El-Kikhia described some of GDF’s “philanthropic” activities (e.g. evacuating families of Taliban supporters from Afghanistan to Tripoli) and noted that they cost billions of euros. However, the foundation’s annual report identified its budget at 11.7 million Libyan dinars (an estimated $9.2 million) with sources only as revenue from unspecified investments and contributions from unnamed individuals, companies and “the Libyan state.” El-Kikhia also observed that public records showed GDF had recently used its financial subsidiary, One Nine Investment International, to acquire 50 million shares of an Irish oil exploration company, Bula Resources, for 900,000 euros. “No citizen in Libya can do such things unless they are a part of the leadership,” he said.

This summer Saif al-Islam was asked about the source of the money paid to the families of the 483 HIV-infected Libyan children following the release of the Bulgarian nurses. At first he replied that he was unsure whether the money came from European Union countries, from Libya, or from both parties. Later, after EU officials denied supplying funds, he announced that Libya had provided the payment.

Who’s Winning at Public Diplomacy?

Why is Muammar Gaddafi, terrorist financier, now posing as a humanitarian, and why has his son, Saif al-Islam, become the poster boy for Libyan philanthropy and good works?

Having agreed to dismantle his weapons of mass destruction program, Gaddafi clearly understands how much he stands to gain from renewed Western trade and investment. This month, following the release of the Bulgarian nurses, Gaddafi secured the French arms deal and a promised visit from the U.S. secretary of state. As crude oil prices soar, Gaddafi also wants to make more deals with U.S. oil companies banned from 1986 until 2004 from operating in Libya. The U.S Department of Energy predicts that by 2013 Libya could increase its oil production by 40% to 3 million barrels a day.

What’s the value of humanitarianism when economic and military might are at stake? Plenty. The Gaddafis, father and son, understand that the West places a premium on ideals like justice and mercy. They are trying to cater to those ideals, albeit in an often bizarre and clumsy way. The Gaddafi Development Foundation is a cynical effort to buy influence under the pretense of charity. It is destined to become more influential in the Islamic world, buoyed by Libya’s growing oil wealth.

The United States has an army of humanitarian programs and legions of foundations and nonprofits involved in winning over the hearts and minds of the Islamic world. The Gaddafi dictatorship can’t begin to compete with America’s “public diplomacy,” can it? Or so we hope.

Eliza Gheorghe is a student at the University of Bucharest, Romania, where she majors in Political Science. She was an intern at Capital Research Center in 2007 under the auspices of The Fund for American Studies.

(photo credit: dmitro2009 / Shutterstock.com)